Thanks to social media, beauty trends often become global phenomena. Despite this interconnectedness, trends in the UK stand apart. While makeup as a category as experienced slowing growth in Canada, Australia and the US since the pandemic, the UK remains a bastion of ‘full glam,’ a style that defined the mid-2010s. What drives these differences, and what does it say about the beauty landscape in Britain?

This episode of The Barefaced Podcast unpacks the economic, cultural, and social factors behind the UK's distinct beauty preferences and what they reveal about the evolution of beauty trends.

Market Interest

British girls love beauty—and it’s evident in the business landscape. Until 2014, fewer than 500 businesses were registered in the UK with ‘beauty’ in their name. But from 2014 onward, that number soared, with over 500 new beauty-focused businesses appearing each year.

With a clear national interest in beauty, the next step is to explore where exactly consumer interest lies. As we discussed last week, Boots stands out as the UK’s largest beauty retailer by a considerable margin. By examining their distribution of newness by category, it reveals where their buying teams anticipate consumer demand to grow and which beauty categories are capturing the most attention.

Makeup dominates, making up nearly 62% of all new beauty products. While colour cosmetics has been recorded as a stagnant category in recent years, with brands shifting their focus to skincare, and more recently fragrance and haircare, the UK market tells a different story.

This is further reflected by the surge in unit sales from 2022 to 2023, with makeup experiencing over twice the growth of the next highest category. This validates boot’s makeup focus and demonstrates how strong the consumer interest in makeup is.

Stylistic Trends

The differences in trends within the British market extend beyond makeup to stylistic preferences as well. British makeup trends center less around minimising the appearance of makeup, focusing instead on bold, high-contrast looks.

These looks usually feature defined brows, sculpted cheekbones, fluffy lashes, and ombre glossy lips. This aesthetic gained international popularity in the mid-2010s, driven by artists like Makeup by Mario through his work with Kim Kardashian—leading to the launch of KKW contour sticks—and Makeup by Ariel through his collaborations with Kylie Jenner, which inspired the launch of Kylie Cosmetics Lip Kits.

However, as the world entered a global pandemic and interest in getting ready and wearing makeup waned internationally, this decline was not mirrored in the UK.

Black Influence

It’s impossible to discuss ‘baddie glam’ without recognising the profound influence of Black culture on beauty trends in the UK. While it stands apart as more than just a trend—and not limited to the UK—it has undeniably shaped the country’s beauty landscape. This impact is evident when comparing TikTok hashtags: despite being more niche, #UKBlackGirlMakeup boasts 22.22% more posts than #UKMakeup, showcasing the pivotal role Black women play in defining UK beauty culture.

I spoke with beauty influencer Katouche (@its.katouche_ on TikTok) about this topic, and she outlined:

“The infamous ‘UK Black Girl Makeup’ is the next evolutionary stage in the highlighting and contouring trends that emerged in the 2010s. For Black women, utilising different products across various tones and shades is essential for maximising a makeup look. Tones and shading play a crucial role in highlighting dark or low-contrast features. For those with hyperpigmentation or lower contrast features, bolder makeup and full coverage are necessary to achieve the desired effect.”

When considering trends that have dominated the cultural zeitgeist since the pandemic, such as the "clean girl" aesthetic—promoting an idealised image of minimalist beauty—it becomes clear that these trends leave little space for Black women to engage in the same way. In contrast, full glam or ‘baddie makeup’ instead allow all to participate.

Class Structure

An additional layer to this is the cost associated with appearing “minimal” or embodying the "clean girl". This becomes particularly relevant when considering the entrenched class structure in the UK, where limited class mobility and inherited hierarchies persist across generations.

Beauty influencer Cee (@Cee.Loux on TikTok) explained to me,

“A key look of the upper classes or the wealthy is looking well-maintained, and this comes at a cost. It’s labour that they can afford to outsource. A part of their look is also understated, reserved, and conservative. I think this is a direct reflection of their financial and economic stability and freedom.”

I thought this was such a brilliant observation of the differences in beauty styling across the UK. Affluent individuals can afford regular skin treatments, allowing them to rely on just a touch of concealer day to day. Similarly, they can invest in regular teeth whitening and may have had braces as a child, while someone with less disposable income might opt for veneers instead.

What’s particularly interesting is how this idea ties back to something Katouche mentioned in our conversation about class pride. She explained that in the UK, “Class pride is more important than class mobility because class is a lot more fixed. So if you’re from ‘Essex,’ you’ll do your makeup in a way that reflects your social context.”

There isn’t one trend uniting the regions; instead, the UK is a country with vibrant subcultures that almost operate as entirely separate entities.

Trending Brands

The UK has a rich history of beauty brands, with some dating back as far as the founding of Rimmel London in 1834. However, something significant shifted in the mid-2010s. A clear contrast emerges when comparing 'old brands' (those established before 2016) to 'new brands' (those launched post-2016).

Brands founded before 2016 tend to be international powerhouses. For instance, Jo Malone’s biggest market is North America, while Charlotte Tilbury and Pat McGrath launched their brands on the back of their international success as celebrity makeup artists. Rimmel, Lush, and The Body Shop have all had a significant presence in the US for over 25 years. In contrast, brands founded after 2016 derive almost all of their revenue from the UK.

Localisation

In recent years, the necessity for brands to go international has dwindled. In the past, brand growth often relied on retailer partnerships and expanding distribution—more partners in more countries meant more customers. However, the downside to this approach was the dilution of localisation, where brands struggled to maintain a strong, tailored connection with local markets.

Now, younger British brands are speaking directly to their home market, allowing them to achieve incredible revenue numbers without the costly and logistically complex process of international distribution.

TikTok Shop

Not only do these brands focus on the UK market, but they also double down on social media, particularly TikTok. In the month surrounding Black Friday, 7 of the 10 highest revenue-driving TikTok Shop brands in the UK were beauty brands.

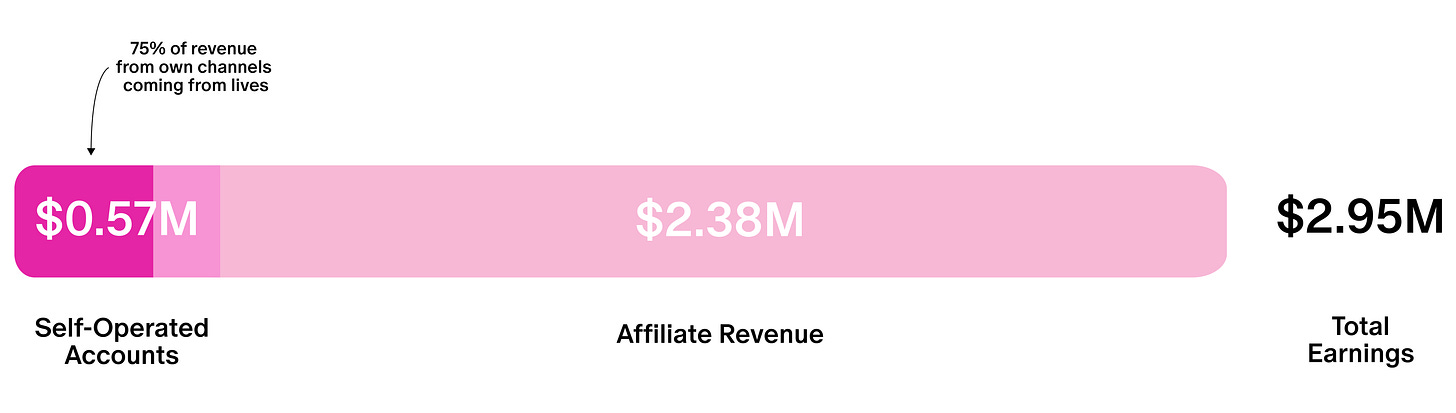

P.Louise is the clear frontrunner, consistently generating US $100k a day, totaling a staggering $2.9M in the last 30 days. What’s remarkable is that 75% of P.Louise’s self-generated revenue on TikTok comes from live sessions hosted on their account.

Yet, even with P.Louise's impressive live-stream revenue, that only accounts for less than 18% of their total TikTok Shop revenue. The majority of their income comes from affiliates—other creators adding shopping links to their content.

TikTok Shop has essentially reinvented infomercials and, in many ways, multi-level marketing (MLMs). This new sales channel allows creators to bypass the traditional, time-consuming process of building brand relationships. The result is a significant shift in the creator economy, where success is no longer solely determined by the size of your following. Instead, it’s about your ability to act as a sales associate.

To me, the brands that focus on localisation, accessible pricing, in-store availability, and organic social media engagement feel as revolutionary as DTC brands did in the mid-2010s.

That concludes this week’s episode! If you enjoyed this post or the podcast, be sure to give it a follow on the streaming platform of your choice and share it with a friend! Thanks for tuning in, and I’ll see you next week!

Share this post